The Guardian view on translation: an interpretative and creative act

Translation is always an interpretation: an act of creation that also, paradoxically, demands a fierce loyalty to the original text. We must cherish our translators for these shy acts of creation, these loyal betrayals. (To translate is to betray, the saying goes, itself a translation of the Italian traduttore traditore.)

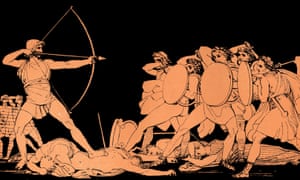

Translators are our guides into other times and territories. They encourage us to leave our own literary shores and to consider other ways of living, other ways of thinking. They can usher into our midst other means of expression, other forms. The literature of one place, of one language, may be reshaped by confrontations with texts from elsewhere. The Aeneid, the most Roman of Roman poems, could not have existed without the Greek Iliad and Odyssey. The sonnet was a southern European form brought to England through Thomas Wyatt’s translations of Petrarch.

In English, there have been at least 60 prominent translations of Homer’s Odyssey, all of them by men. Now comes the first published version by a woman: Emily Wilson, professor of classics at the University of Pennsylvania. (This in itself is a curious anomaly: Anne Dacier’s French version was published in 1708. In Italian, until recently the best-read translator of Homer’s epics, familiar to generations of schoolchildren, was Rosa Calzecchi Onesti, who died in 2011.)

Wilson, a considerable scholar of Greek, has turned the received wisdom about the interpretation of a poetic line inside out. And that’s a good thing – just as it was a good thing when, 30 years ago, Martin Bernal, the author of Black Athena, swept into the world of classical scholarship with his provocative thesis on the African origins of Greek culture that – notwithstanding the controversy surrounding his claims – had the effect of forcing scholars to recognise the limitations of reading the ancient world from the confines of a white, male, Eurocentric perspective.

The joy of Homer is precisely the generosity and suppleness of the material, the fact that it resists being read in a single way. That’s why a new kind of guide through his wild landscapes, across his wine-dark seas, is to be welcomed.

This post originally appeared on The Guardian