For most of you, customers can come to you from any country in the world. That means all of your potential customers — the people visiting your website, reading your blog posts, and clicking on your calls-to-action — might speak a myriad of different languages or live in totally different time zones. Once they reach your content, how well will it resonate with them?

As your international traffic grows, you’ll want to be sure that you can convert that traffic into leads — and that means keeping your international visitors in mind every time you write about a holiday or publish data with certain units of measurement.

In this post, I’ll share some tips to help you create content that appeals to your entire audience, no matter where in the world they come from.

11 Tips for Making Your Content International

1) Identify culturally rooted content.

When writing for a global audience, we should all be more aware of how our own cultural norms creep into our content. Each time you write a blog post or some other piece of content, imagine you’re reading it out loud to someone who is visiting your country for the very first time. Did you include any terms or concepts that would require additional context or explanation? Look for culturally rooted items in your content, and be sure to add a quick note or explanation for your international viewers.

For example, let’s take a look at this blog post about Thanksgiving Break:

The content of this post isn’t just helpful to the Americans and Canadians who celebrate Thanksgiving. The advice could just as easily help marketers who are getting ready to take a day or two off to celebrate many holidays around the world. And yet, many of the references — to turkey, pie, and so on — require North American cultural knowledge. In fact, the featured image itself might not be attractive for people who have never seen, let alone eaten, pumpkin pie.

Here are some examples of culturally relevant items and explanatory notes you could add to the post:

- Thanksgiving = a national holiday celebrated by families in the USA and Canada

- Cranberry sauce =

a typical food served on this holiday

- Warm fireside chats = a typical family activity associated positively with this holiday

- Pumpkin pie = a

traditional holiday dessert

Depending on your goals, you might decide to translate your post into other languages. In translated versions, you could swap out any country-specific holiday references for ones that are relevant for each target group. Or, you might simply decide to offer readers a different version of the post that is relevant to more people than a single holiday in just one region.

2) Be aware of seasonal references.

A blog post published in the summer in the Northern Hemisphere might talk about ice cream and vacations from school — but during that time, the poor folks the Southern Hemisphere might be battling snowstorms and bitter cold.

I’m not saying you should never write about the seasons — but you will want to be aware of your seasonal references and how they might be interpreted by folks on the other side of the globe. If someone on your team is in charge of localizing all your content, you could flag the seasonality of a given blog post, for example, so that “localizer” can update the content. Or, publish and promote it at a more appropriate time of year for the target markets.

Here’s an example of a blog post that references a “summer sales slump”:

If you were to translate the content in the blog post above into other languages, you might decide to swap out the references and images so it references the correct time of year for your target audience. Or, you might just adjust the content to reflect the warmer season in their country, and then select a date for publication that coincides with that time of year.

3) Watch for units of measure.

Do you go the extra mile for your customers? Maybe you shouldn’t if they prefer kilometers. Rather than introduce units of measure that might be specific to just one set of countries, you might consider simply tweaking the content slightly to make it more global-friendly.

Here are two easy ways to improve written content for international readers:

- Use a unit of measure that’s is relevant to more people: “… within a five-block radius of your restaurant …”

- Show alternate units of measure: “… within a one-mile (1.6 km) radius of your restaurant …”

- For a more advanced solution, use a custom field to automatically display the appropriate unit of measure appropriate for the visitor’s country (as stored in a database) or using geo detection based on the user’s browser with a smart default if no browser-based language or geo data is available.

4) Mind monetary references.

A “millionaire” in some countries might be anyone with a few thousand dollars, depending on currency conversion. Likewise, someone who earns “six figures” might actually not be doing so well. Americans know implicitly that this is an annual income amount, but many countries think in terms of monthly salaries instead.

Consider this example, in which we’ve used the phrase “six-figure income”:

If it won’t dilute the power of the text, consider using a synonym or a replacement in the source text to make it universally understood. For example: “… who earn in the highest income brackets …” or “… who have high levels of discretionary spending …”

Or, annotate the text to make it clear that by “six-figure income,” you’re actually referencing a high-wage earner in the United States.

5) Create CTAs with translation in mind.

You want your international visitors to convert just as much as your national ones – so it’s especially important to double-check that your CTAs will be effective for other languages and countries.

If you’re planning to translate content at some point, you can “pseudo-localize” by adding 40% more characters to the text to make sure it will fit when translated into most languages. Also, you’ll want to reduce surrounding graphics, and leave more space on buttons, to ensure text will fit when localized.

Ideally, every CTA should separate the text layer from the image layer to enable quick translation. This is also a best practice for SEO in general, as text embedded in images isn’t usually picked up by search engines. If you can’t separate the text layer from the image layer, any images that contain text will need to be created for each language separately, which is time-consuming and expensive.

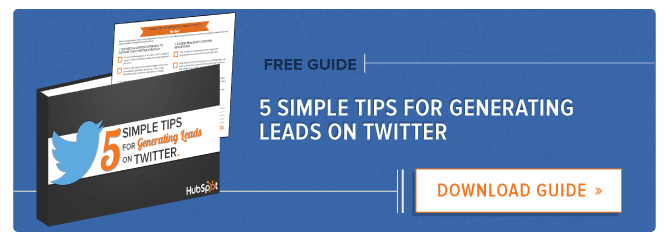

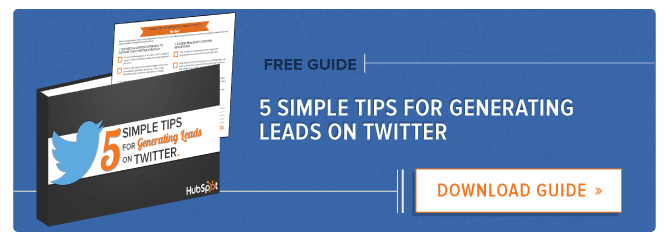

When designing a CTA that will later be localized, leave 40% more space than you would normally leave to allow for text expansion in other languages. Here’s one example:

Would “Download Guide” look nice on this image if it were nearly double the number of characters? Probably not. In fact, it might not fit at all. Resizing the screenshots slightly will free up a bit more space for the text. The font size might also need to be adjusted, or the surrounding box might need to be enlarged.

Another option? When translating, tell the translators to feel free to substitute “Download Guide” with something that might be shorter in another language, like “download” or “access” or “show me.” Otherwise, most translators will be faithful to the source language instead of using a term that might actually look and fit better.

6) Observe date differences.

Not every country has a weekend on Saturday and Sunday. Also, some countries use a lunar-based calendar. If you can swing it in a way that sounds natural, try to avoid references like this in your writing.

For example, the first line of the blog post below reads, “It’s already Sunday?! Man, the weekends fly by so quickly in the summer.”

Again, “Sunday” doesn’t mean the end of the weekend for everybody. In this case, a simple text swap is all that’s needed. You could replace that line with something like, “The weekend’s nearly gone?! Man, it always flies by…”

7) Avoid images with text.

If you’ve gone through the trouble of translating a blog post into another language, you’d never want to accompany that translated post with an image in the original language. Either your readers will get confused, or they’ll feel like the content wasn’t designed for them.

When possible, choose a source image that will resonate universally. If you really need one with words in it, alert the translator of what other types of images might work instead, so they can select another.

For example, the featured image in the blog post below shows a hand with the word “STOP” written on it:

Remember, although the hand sign might look familiar, the word “STOP” isn’t the same in every language. Instead, opt for a more universal symbol that accomplishes the same thing, like a stoplight.

8) Give translators the tools and permissions to adapt liberally when needed.

Sometimes, there might be elements within a piece of content that might not make perfect sense for the target audience. In these cases, it’ll be important to let the translator know what to do and how far they can go to customize it for a specific audience.

For example, if you have a diagram within a post, can the translator delete the diagram and simply describe it instead with words? Or do they need to adopt the diagram with a localized version? Give them clear instructions.

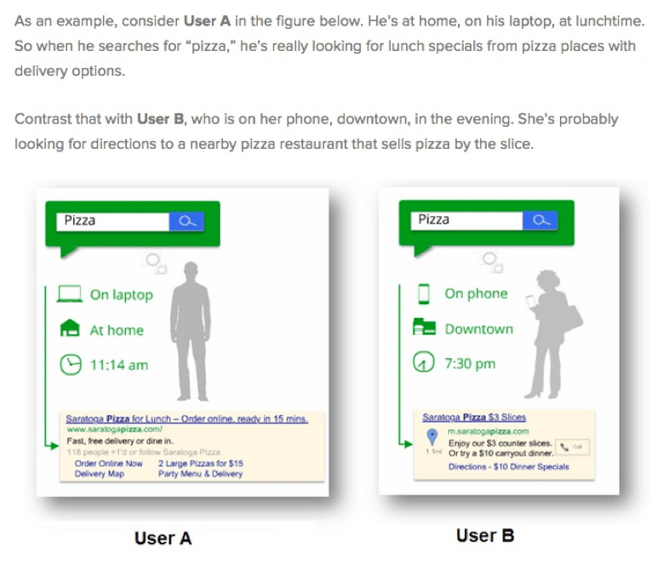

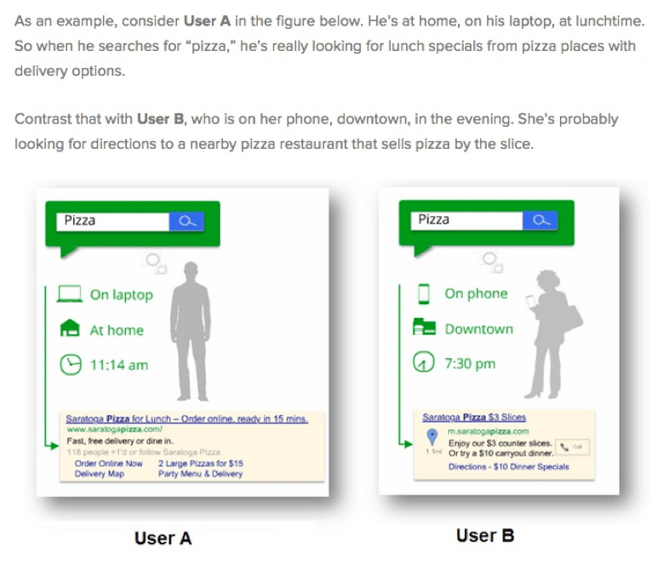

Take a look at this screenshot from a blog post we wrote optimizing AdWords campaigns for desktop and mobile:

Someone translating this post might be able to swap these diagrams out with a description. Or, if given instructions and the original image files, they could adapt these images to a new language. Finally, remember that something like “pizza” may not be relatable to, say, a Japanese audience — it might be more appropriate to use an example like “sushi” instead.

In this example, a translator would also note that the time format used in the image will vary depending on location.

9) Translate keywords properly.

Keywords that rank well in your country may not rank well in other countries — and their direct translations might not, either. But finding the right keywords and optimizing the blog post for these keywords will be worth the SEO boost.

When you’re negotiating translation costs as part of localizing content, you may want to discuss the selection of a relevant keyword for the source country. They can usually do this by using web-based tools to research keywords.

10) Create a feedback loop.

Creating global content is a team effort. Any way that the authors of content in its original language can make the translation process easier for the translators –and vice versa – will only speed up the localization process in the future.

Share any comments translators make with the source content team to help them stay aware of anything inhibiting the translation process, or that might help them select better terms in the future. They don’t need to be hypersensitive to localization, but it’s good for them to keep some examples top-of-mind. Over time, this will make everyone’s jobs easier.

Here’s an example of a piece of content flagged by a Japanese translator:

The word “exposure” might carry multiple meanings and possible translations in Japanese – some of them negative. “Visibility” might be a better alternative that lends itself to less confusion.

Here’s another example, this time from Brazil:

The term “marketing agency” isn’t common in some languages and countries. The translator wants to ensure it’s OK to use a local equivalent instead.

11) Consider crediting your translators.

Translators can be great advocates for their own work, especially if they have a bio or online resume that points others to examples of their work. Consider crediting them by including something like “translated by [name]” or “adapted by [name]” at the bottom of the post. Doing this will make it clear to readers that the content was adapted, therefore setting the right expectations for your international visitors. It’ll also help you develop good relationships with your translators.

These tidbits are just the tip of the international iceberg, but following them will help you begin creating content that resonates beyond just your own local borders. After all, your next customer could be anywhere.

What tips do you have for creating content that appeals to an international audience? Share with us in the comments below.

Original article published here: Hubspot.com